In an era where political longevity is often equated with stability and success, a closer examination reveals a striking contrast: some leaders who held power for just a few years implemented transformative reforms, while others who governed for decades left legacies marred by stagnation, corruption, and unmet potential. This pattern is particularly evident in Africa, where brief tenures have sometimes yielded remarkable progress, but it extends globally, with fixed-term systems like the United States presidency providing fertile ground for focused achievements. Historical analysis underscores that brevity in office does not preclude impact indeed, it may foster urgency and innovation.

African history offers compelling examples of leaders who, despite serving approximately four years or slightly more, enacted sweeping changes that continue to resonate. Thomas Sankara, who led Burkina Faso (then Upper Volta) from 1983 to 1987 before his assassination, stands out as a beacon of self-reliance. In his short time, he spearheaded a nationwide literacy campaign, vaccination drives that slashed infant mortality from 20.8% to 14.5%, and the planting of over 10 million trees to battle desertification. Sankara also banned female genital mutilation and forced marriages, championed women’s rights, and rejected IMF loans to prioritise agrarian reform and anti-corruption efforts, earning him iconic status across the continent.

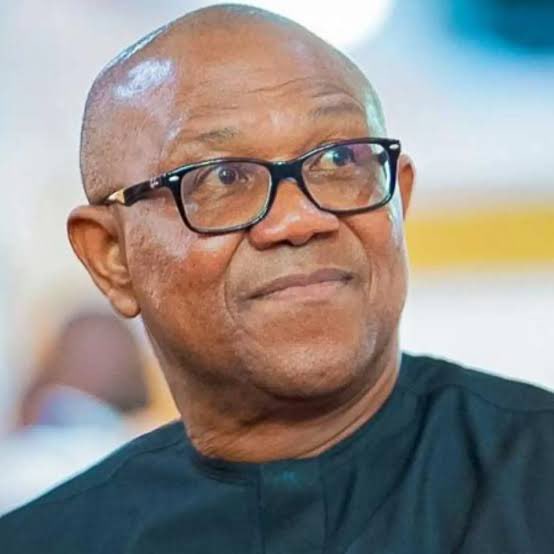

Similarly, Goodluck Jonathan’s single elected term in Nigeria from 2011 to 2015 saw the country’s GDP rebased to become Africa’s largest economy. His administration advanced rail modernisation, privatised the power sector to enhance electricity access, and boosted agricultural production, reducing food imports. Despite facing corruption and security issues, Jonathan facilitated a smooth democratic handover, marking a step towards economic diversification.

Nelson Mandela’s five-year presidency in South Africa from 1994 to 1999, during which he opted not to seek re-election, symbolised reconciliation after apartheid. Through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, he fostered national unity, established democratic institutions, and promoted human rights, laying groundwork for policies to tackle inequality and poverty. Joyce Banda, Malawi’s president from 2012 to 2014 following her predecessor’s death, devalued the currency to attract aid, combated corruption by sacking officials and repealing oppressive laws, and improved food security, emerging as a trailblazer for women’s leadership in Africa.

Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s leader from 1960 to 1966 until a coup ousted him, guided the nation to independence the first in sub-Saharan Africa and invested in infrastructure like the Akosombo Dam, education, and industrialisation, inspiring pan-African movements despite later economic hurdles.

Outside Africa, examples abound, especially in the United States, where presidential terms are constitutionally limited to four years, encouraging decisive action. James K. Polk (1845–1849) orchestrated America’s greatest territorial expansion, annexing Texas, securing Oregon through treaty, and acquiring California via the Mexican-American War, while lowering tariffs and establishing an independent treasury to spur trade.

Jimmy Carter (1977–1981) brokered the Camp David Accords for Middle East peace, prioritised human rights, deregulated key industries, and created departments for energy and education, alongside vast environmental protections in Alaska. George H.W. Bush (1989–1993) navigated the Cold War’s end, led the Gulf War coalition, enacted the Americans with Disabilities Act and Clean Air Act amendments, and initiated NAFTA for economic ties.

Rutherford B. Hayes (1877–1881) peacefully concluded Reconstruction, reformed civil service to curb corruption, and upheld diplomatic treaties by vetoing discriminatory immigration laws.

Yet, this narrative flips when examining leaders who clung to power for 4 to 50 years but failed to deliver meaningful positive change, often exacerbating problems through poor governance. In Africa, such cases are rife amid resource wealth and authoritarianism. Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo has ruled Equatorial Guinea since 1979, 46 years—yet oil riches have not trickled down; corruption and nepotism keep most citizens in poverty, with scant investment in health or education.

Paul Biya’s 42-year grip on Cameroon since 1982 has yielded economic stagnation, with poverty exceeding 37%, rigged elections, and repression of minorities. Denis Sassou Nguesso’s 38 years in the Republic of the Congo have seen oil dependency without diversification, corruption, and over half the population in poverty.

Robert Mugabe’s 37 years in Zimbabwe (1980–2017) began with promise but devolved into hyperinflation, violent land grabs, and economic ruin. Mobutu Sese Seko plundered the Democratic Republic of the Congo for 32 years (1965–1997), creating a kleptocracy that collapsed infrastructure and entrenched poverty.

José Eduardo dos Santos’s 38 years in Angola (1979–2017) left extreme inequality despite oil booms, with corruption siphoning wealth. Blaise Compaoré’s 27 years in Burkina Faso (1987–2014) featured repression and stagnation, ending in uprising. Yahya Jammeh terrorised The Gambia for 22 years (1994–2017) with eccentric policies and economic mismanagement. Omar al-Bashir’s 30 years in Sudan (1989–2019) involved genocidal wars and economic woes, culminating in his ouster.

This trend transcends Africa. Alexander Lukashenko’s 31 years in Belarus since 1994 have brought rigged elections, corruption, and economic reliance on Russia. Emomali Rahmon’s 33 years in Tajikistan since 1992 perpetuate poverty and nepotism. Bashar al-Assad’s 25 years in Syria since 2000 have wrought civil war, economic devastation, and mass displacement. Nicolás Maduro’s 12 years in Venezuela since 2013 have triggered hyperinflation, GDP collapse, and a refugee crisis.

These contrasts prompt reflection on governance: short terms may compel leaders to act swiftly and legacy-mindedly, while prolonged rule risks complacency and abuse. As global democracies evolve, the lesson is clear—impact stems not from duration, but from vision and accountability.