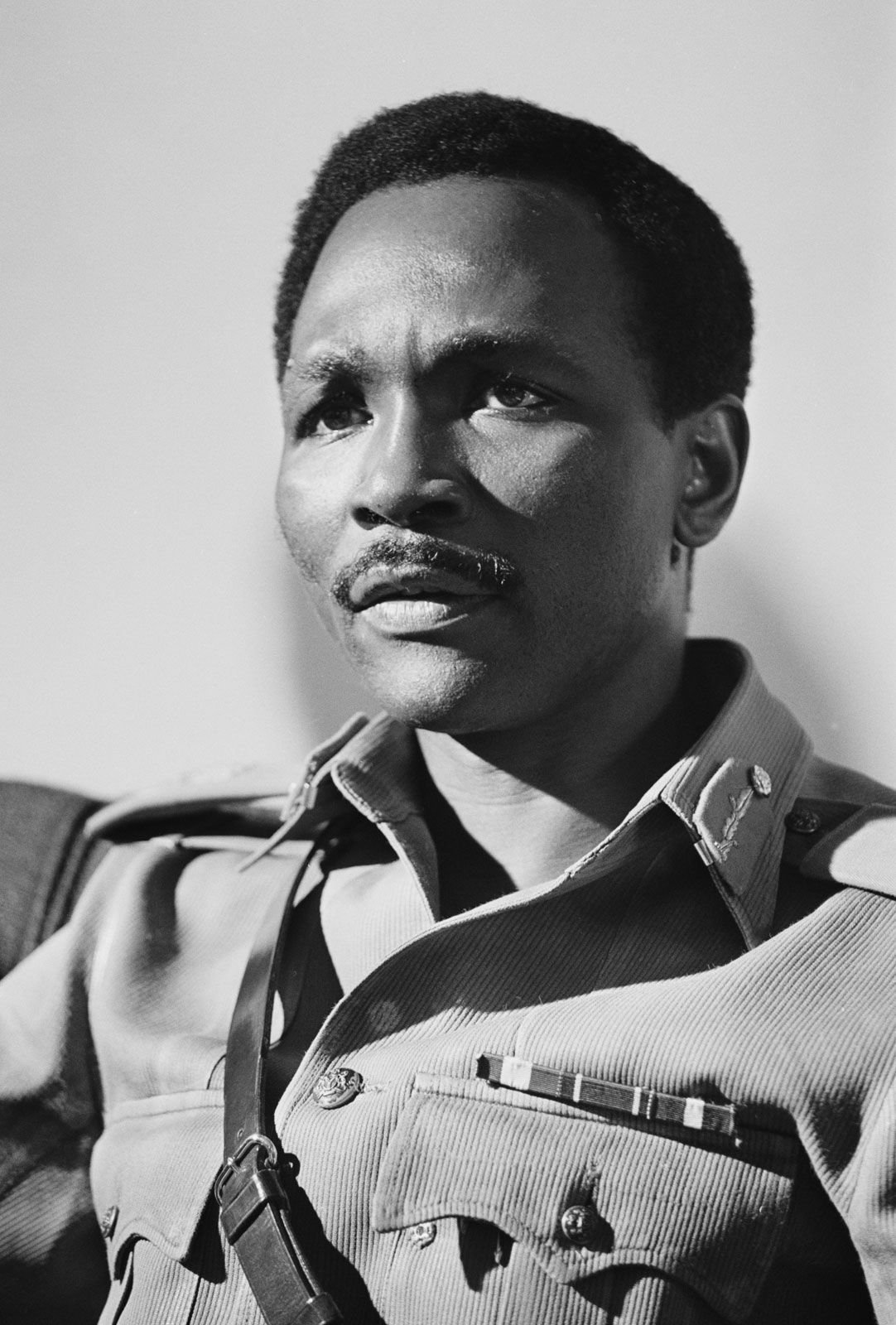

In a recent interview with Arise News, conducted by Charles Aniagolu, former Nigerian Head of State, General Yakubu Gowon, revisited the contentious Aburi Accord of 1967, shedding light on the events that preceded the Nigerian Civil War. The interview, which aired on Wednesday, June 18, 2025, provided a platform for Gowon to articulate his perspective on the accord’s failure, a pivotal moment in Nigeria’s history that many believe could have averted the devastating conflict.

Gowon revealed that upon returning from the Aburi meeting in Ghana, he was incapacitated by a severe fever, which delayed his ability to issue an immediate statement on the accord. This admission raises questions about the preparedness and responsiveness of the federal government during a critical juncture. The Aburi Accord, a series of agreements reached between Gowon and Eastern Region leader Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, was intended to address the escalating tensions that threatened Nigeria’s unity. However, Gowon’s illness arguably hindered the timely implementation of these agreements, allowing misunderstandings to fester.

Further complicating matters, Gowon acknowledged that Ojukwu did not attend a subsequent meeting held in NIFOR, Benin, citing safety concerns, and failed to send a representative. This absence, Gowon suggested, undermined efforts to clarify and consolidate the Aburi decisions. The lack of Ojukwu’s participation in this crucial follow-up meeting highlights a missed opportunity for dialogue, which could have been instrumental in preventing the drift towards war.

Gowon’s admission that he did not bring senior civil servants to the Aburi conference, in contrast to Ojukwu’s well-prepared entourage, is particularly striking. Ojukwu’s strategic approach, bolstered by the presence of seasoned civil servants and a clear set of demands, arguably gave him an advantage in the negotiations. This disparity in preparation raises the question of whether Gowon was naive in his approach to such a significant diplomatic engagement. The absence of a robust advisory team might have left Gowon vulnerable to Ojukwu’s more structured strategy, potentially influencing the outcome of the discussions.

Moreover, Gowon’s change of stance following consultations with federal permanent secretaries, notably the Benin-born Prince Solomon Akenzua, is a point of contention. Akenzua, a prominent civil servant at the time, reportedly expressed alarm at the implications of the Aburi Accord, particularly its potential to weaken the federal centre and pave the way for confederation. This perspective likely influenced Gowon’s decision to reinterpret the accord, a move that Ojukwu perceived as a betrayal. The shift in policy, driven by internal advice rather than a direct renegotiation with Ojukwu, suggests a lack of commitment to the spirit of the original agreements and raises questions about the sincerity of the federal government’s intentions.

In the interview, Gowon also touched upon a personal encounter with Buka Suka Dimka, the mastermind behind the 1976 coup attempt against him. Dimka visited Gowon in London, but Gowon expressed concern over Dimka’s communist ideologies, which he found alarming. This revelation adds another layer to Gowon’s narrative, illustrating his ongoing engagement with figures from Nigeria’s turbulent past and his wariness of ideological threats.

Critically, Gowon’s reflections on the Aburi Accord invite scrutiny of his leadership during a period of national crisis. His naivety, if not fully acknowledged, is implied by his lack of preparation and the subsequent reliance on advisors who may have had their own agendas. The failure to insist on the details of the accord or to engage in a robust post-Aburi dialogue with Ojukwu underscores a missed opportunity for peace. The change of mind following consultations with the permanent secretaries, particularly Akenzua, suggests a reactive rather than proactive approach, which ultimately contributed to the breakdown of trust and the escalation of conflict.

As Nigeria continues to grapple with its historical legacies, Gowon’s interview serves as a reminder of the complexities and consequences of leadership decisions during times of crisis. The Aburi Accord remains a symbol of what might have been, a potential path to unity that was derailed by miscommunication, mistrust, and a lack of preparedness. For historians and policymakers alike, Gowon’s account offers valuable insights but also prompts a reevaluation of the decisions that shaped a nation’s destiny.