Lagos, Nigeria – 14 August 2025

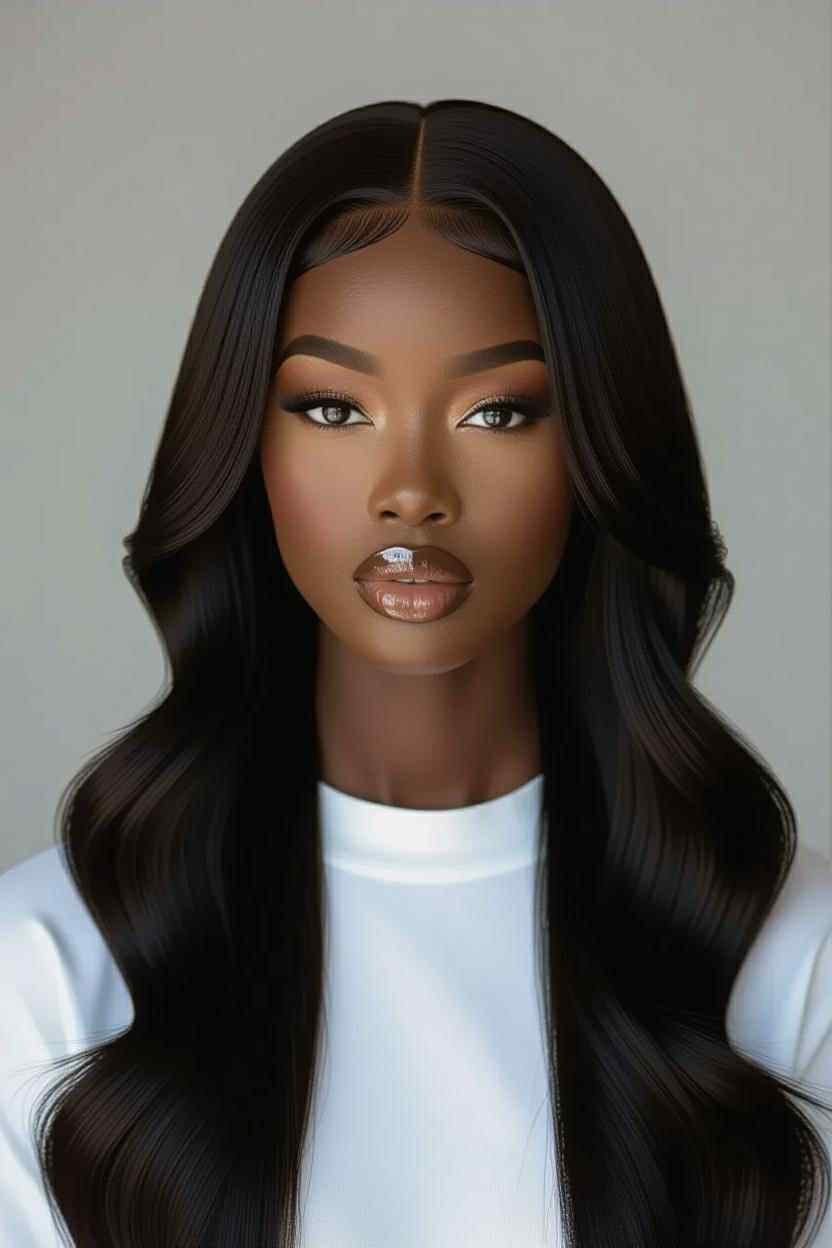

In a continent rich with diverse traditions and natural beauty, a growing chorus of voices is questioning the widespread adoption of wigs made from non-African hair, labelling it a symptom of a deeper “crisis of identity” among African women. Critics argue that the practice, which sees women donning straight or wavy hair sourced primarily from Asian and European donors, perpetuates self-doubt and erodes cultural pride. This sentiment, echoed in social media discussions and academic analyses, highlights a tension between modern beauty standards and traditional African aesthetics.

The debate gained fresh momentum from a provocative statement circulating online: “It is ONLY in Africa that their WOMEN wear hair belonging to living/dead Asian and white women, boast about it, and call it bone-straight. There is a crisis of identity among African women. The explosion of wig-wearing is dehumanising. Stop and guess for a second: seeing an African man wearing a white or Asian man’s hair wig. How would you see that African man? Why is it then normal for African Women to wear Asia women’s hair & gloat about it? If you must wear a wig, wear an Afro-looking synthetic wig, not a human hair wig… Wear a Bob Marley cornrow type of synthetic hair (not natural hair belonging to a dead Asian or white woman). African women must desist and regain their pride and identity.”

This viewpoint resonates with broader critiques of Eurocentric beauty ideals imposed on black women through historical colonialism and globalisation. Scholars and activists point to centuries of denigration, where African hair textures often coiled, kinky, or curly were deemed “unprofessional” or “inappropriate” in workplaces and societies influenced by Western norms. For instance, in professional settings, black women have long faced pressure to straighten their hair or opt for wigs to conform, a practice rooted in racial biases that persist today.

Prominent figures have amplified these concerns. Nigerian author and influencer Reno Omokri has urged African men to compliment women on their natural hair and dark complexions, warning of an “epidemic” of self-hatred where sisters “do not believe they are beautiful unless they put hair from women of other races on their heads.” He highlighted Nigeria’s staggering $200 million annual import of human hair from Asia, arguing that funds could be better directed towards education and development rather than reinforcing foreign beauty standards. Similarly, Zimbabwean marketing strategist Rutendo Matinyarare criticised beauty pageants for favouring contestants with non-African wigs, suggesting it conditions women to view their natural hair as inferior.

Economic and cultural dimensions underpin the issue. The global wig industry, valued at billions, thrives on demand from African markets, with South Korea historically emerging as a key exporter during the Cold War era, supplying wigs that blended Korean-American entrepreneurship with African-American hairstyles. Yet, this boom has sparked accusations of exploitation and cultural erasure. Online commentators decry the irony: while African women invest heavily in “bone-straight” or silky textures, producers in Asia rarely wear such styles themselves, viewing them as exports tailored to foreign tastes.

Not all perspectives align with the critics. Defenders of wig-wearing emphasise personal choice, protective styling benefits, and the evolution of beauty as a form of self-expression. In academic circles, discussions explore how black women’s hair decisions reflect a “politics of being,” where weaves and extensions serve as armour against societal scrutiny rather than outright rejection of identity. One study notes that while some women straighten or extend their hair to mimic Caucasian styles, this is often a pragmatic response to discrimination, not inherent self-loathing. Moreover, global trends show wig use crossing racial lines, with white and Asian women increasingly adopting them for fashion, challenging the notion that it’s uniquely an African “crisis.”

Health implications add another layer. Prolonged wig use, especially glued styles, can lead to traction alopecia or scalp damage, while skin-lightening creams often paired with Eurocentric beauty pursuits pose risks of cancer and organ harm. Advocacy groups like those promoting the “natural hair movement” encourage embracing afros, braids, and locs, drawing inspiration from icons such as Bob Marley to reclaim pride.

As social media fuels the conversation, with posts labelling wig dependency as “self-hate” or “inferiority complex,” calls for change grow louder. Experts suggest education on African heritage and policy shifts, such as banning discriminatory hair policies in schools and offices, could help. Ultimately, the debate underscores a universal truth: hair is more than aesthetic, it’s a symbol of identity, resilience, and the ongoing struggle against imposed ideals.